Officials can only be impeached for corruption or crime. Does a Wisconsin Supreme Court’s justice comments about the state’s political districts rise to that level?

By Peter Cameron, THE BADGER PROJECT

Could language in the state’s Constitution allow Republicans to sideline the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s new left-wing majority?

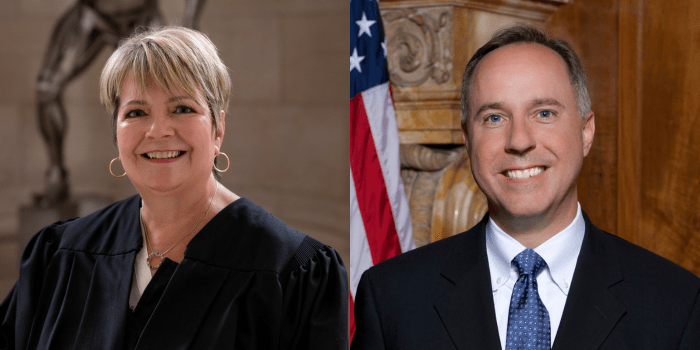

The left-leaning Janet Protasiewicz overwhelmingly won a seat on the court in the spring giving liberals a majority there for the first time in years. The court could decide on some major issues soon, like redistricting and abortion.

How far would Republicans go to protect the political districts they drew that give them maximum political advantage in the state legislature? They have controlled that body almost exclusively since 2011. The Constitution contains a wrinkle that might help them do that, but more importantly, might not let them get there in the first place.

Before she even took her seat, at least one Republican floated the idea of impeaching and removing Protasiewicz. The GOP has the needed simple majority in the state Assembly and a supermajority in the state Senate to do so, but is only allowed to impeach government officials for “corrupt conduct in office, or for crimes and misdemeanors,” according to the Wisconsin Constitution.

On a right-wing radio program earlier this month, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, the top Republican in the state, told host Meg Ellefson: “If there’s any semblance of honor on the state Supreme Court left, you cannot have a person who runs for the court prejudging a case and being open about it, and then acting on the case as if you’re an impartial observer.”

Protasiewicz referred to Wisconsin’s political districts as “rigged” during a campaign debate, then added she couldn’t say how she would rule on a particular case.

Justices frequently refrain from commenting on issues their court could rule on in the future, but that line has blurred as the Wisconsin Supreme Court has become more partisan and politicized.

Justices also sometimes recuse themselves, i.e. refrain from ruling, on cases where they have an interest.

“It is not at all clear that the legislature has the power to impeach a justice merely because of a disagreement over recusal,” said Robert Yablon, an associate professor at the UW Law School. “Politics in Wisconsin has been contentious for a number of years, but going down the impeachment road would be a serious escalation of partisan conflict.”

He noted only one justice in the state has ever faced impeachment, back in 1853, and he was acquitted.

“Judicial impeachment is largely uncharted territory in Wisconsin,” Yablon said.

Setting aside the debate of whether this comment rises to the level of “corrupt conduct in office,” especially considering she made it before she was in office, Republicans have the numbers to impeach and remove Protasiewicz.

But Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, could simply reappoint her, or another person, to the position, allowing the left to maintain their majority.

However, the state Constitution says this on the matter: “No judicial officer shall exercise his office, after he shall have been impeached, until his acquittal.”

So could the GOP impeach Protasiewicz in the state Assembly, but take no action in the state Senate, to keep her in legal limbo?

Ed Miller, a political professor emeritus at UW-Stevens Point and a longtime watcher of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, said in an email that this “seems correct.”

Such impeachment gamesmanship would be “unprecedented,” Yablon noted, and it’s uncertain what would happen next.

“The governor could conceivably assert that the legislature’s actions have created a temporary vacancy on the court, allowing him to appoint an interim replacement,” he continued. “Or perhaps a court could conclude that the state constitution doesn’t permit delay tactics and that the Senate’s inaction should be treated as an acquittal.”

Protasiewicz could also just resign, freeing up the seat for Evers to reappoint, Miller said. Or a suit could be filed in federal court to let them sort it all out, he added.

But Democrats would like to have the state’s political maps adjusted as soon as possible, and the 2024 election is fast approaching. Delays could push redistricting changes to 2026. Left-wing Justice Ann Walsh Bradley is up for reelection in 2025, and right-wing Justice Rebecca Bradley is up for reelection in 2026.

Miller also noted the Wisconsin Supreme Court has “failed to adopt a recusal rule,” and remembered that in 2017, the conservative majority on the court, which included current justices Annette Ziegler and Rebecca Bradley, rejected an appeal from a group of retired judges to adopt such rules regarding cases brought by parties who had donated to the justices’ campaigns. The Wisconsin Democratic Party supported Protasiewicz with millions of dollars in her successful campaign, and has much to gain from the redistricting lawsuits that have been filed in the state since she took office.

The last time redistricting came before the court

Despite being a purple state where Democrats regularly win at the statewide level, the GOP has controlled the state legislature with huge majorities for years.

When the Wisconsin Supreme Court was controlled by a 4-3 conservative majority last year, before Protasiewicz won and took her seat, the court made a decision that required the new maps take a “least changes” directive from the old maps. Because the previous districts had a strong partisan slant, the court’s ruling was nationally unprecedented, Yablon said. When courts across the country have issued this directive in the past, the basis maps have little to no partisan slant.

After the U.S. Supreme Court, which is controlled by a right-wing majority, intervened and gave new guidance, the Wisconsin Supreme Court then chose to enact state legislative maps submitted by Republicans. The state’s high court also chose to enact Congressional districts submitted by Democrats, giving the political left a minor victory.

In every major decision the court made in the most-recent redistricting case, the right-wing and left-wing blocs were evenly split, and right-leaning Justice Brian Hagedorn, who sometimes sides with liberals, was the decisive vote.

Per the U.S. Constitution, state legislatures must redraw their political districts every ten years, after the Census.

In Wisconsin, the governor and legislature must agree on the maps. Otherwise, the courts must intervene.

In recent decades when state government was split and could not agree on political districts, the Wisconsin Supreme Court had refused to involve itself in redistricting for a variety of reasons, including that they had no mechanism to create the maps, because they were an appeals body and not a fact-finding body, and because redistricting is a political act and the state court is elected, Miller said. For those reasons, the court has repeatedly kicked the issue to the federal courts.

But in 2021, the right-wing bloc on the court decided to break from that tradition, and ended up making rulings that mostly benefited Republicans.